Throughout history, although women did not always have the inventions of modern tampons and pads, they still found ways to deal with their monthly menstrual cycles. Women have been known to use rags, cotton, sheep’s wool, rabbit fur, knitted pads, and even grass to hinder the flow of menstrual blood.3 These practices varied from culture to culture, but overall, women of the past found ways to prevent periods from interfering with their day to day lives. The purpose of tampons and pads is a practical one: to catch or absorb menstrual blood so it does not flow freely. However, today and for the past several decades, there has also been a social element to periods for women, which involves keeping menstruation hidden. To be seen showing menstrual blood, such as through stains on clothes, can be an embarrassing experience for some women. For example, leaking can occur if a pad or tampon is not absorbent enough for the level of menstrual flow, or even when physical activity moves a pad into the wrong position. Besides the practical objective of catching menstrual blood, the goal of modern tampons and pads is to make periods discreet, dependable, and relatively effortless. In order to achieve this feat, tampons and pads have come a long way in development since their creation.

Ancient History

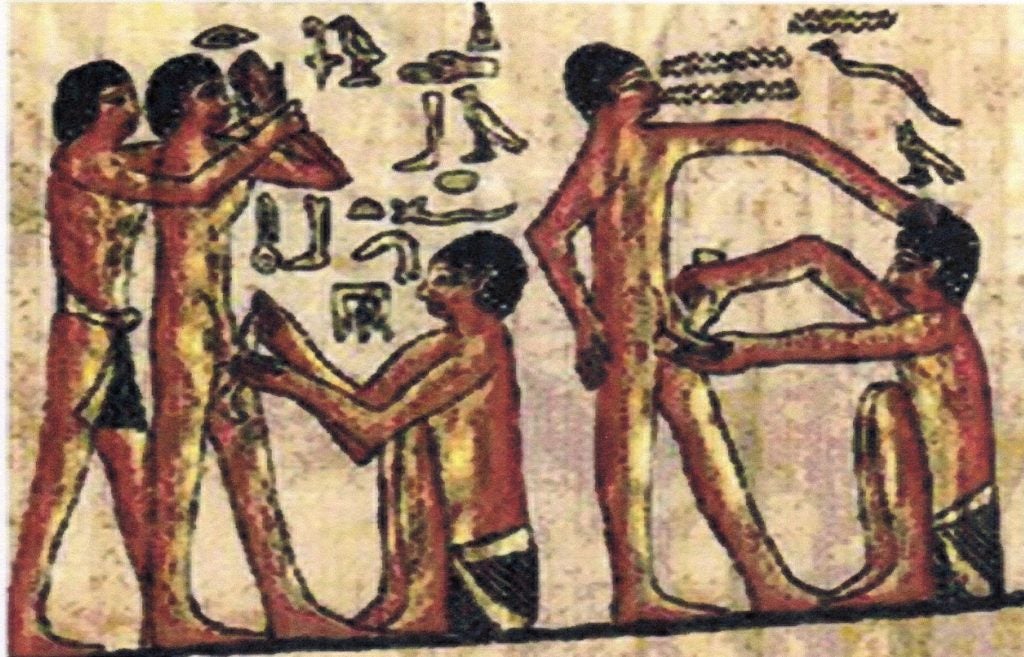

The use of tampons and pads dates back to ancient times, starting with the Egyptians. Ancient Egyptians used materials like papyrus and lint to make tampons, while the ancient Greeks and Romans wrapped lint around wooden pegs to create tampons. In ancient Japan, women used paper to absorb blood, while Native Americans made pads out of moss and buffalo skin.1 Additionally, ancient Romans used wool, and absorbent moss was also utilized by ancient Africans and Asians.2

Fascinatingly, in many parts of the ancient world, menstruating women were associated with mystery, sorcery, and magic.3 On the other hand, in Mayan mythology, menstruation was seen as a punishment from the Moon goddess, and it was believed that her menstrual blood could magically transform into snakes, poison, or diseases.3 In biblical times, menstruation was seen as unholy, which led ancient Hebrews to cast out menstruating women into seclusion where they remained separated from society for seven “clean” days.3 For Christians in the medieval era, menstruation was commonly associated with religious shame, and medieval European women went to great lengths to hide their periods, from wearing herbs to hide the odor of blood, to taking medicines to stem a heavy flow.3 However, these women did not often seek pain relief because it was not permitted by the Church, where people believed that God wanted cramps to be a reminder of Eve’s Original Sin.3 Aside from using the occasional rag or absorbent garment, hence the birth of the phrase “on the rag,” medieval European women would often bleed directly onto their clothes. In medieval times, it was more common for women to have several children rather than just one or two, and this impacted how often these women would actually get their period. During pregnancy and while lactating, women do not menstruate, so young women who had 5-6 children would lose about ten years of their “menstrual life” over time (from menarche to menopause).1 Therefore, medieval European women getting their period and bleeding onto their clothes was not incredibly common or as intrusive to daily life as it might be today.

Tampons and pads often had multiple uses aside from absorbing menstrual blood, such as ancient Egyptians who dipped lint tampons in honey and lactic acid to prevent pregnancy. At that time, lactic acid was thought to act as a spermicide, so tampons would double as period devices as well as contraceptive devices.2 During World War I, where American soldiers were often lacking supplies, nurses repurposed tampons and pads as absorbent bandages, demonstrating their versatility once again.1

Modern History

In 1879, as hygiene standards started to improve during the era of the Industrial Revolution, concern grew over whether it was sanitary for women to bleed onto their clothes, and some doctors worried about the risk of infection. Then, a new contraption called the Hoosier sanitary belt entered the market. This was a metal belt that wrapped around the waist with washable pads that women could purchase.3 Not long after, in 1888, the first disposable menstrual pads became commercially available. They were developed by the company Johnson & Johnson, who would later go on to sell the brand Tampax.3 These pads were originally sold in maternity kits made by Johnson & Johnson until women encouraged the company to sell them separately. Being able to throw away pads after using them was a big deal for women, especially considering the resources available to them at the time. There were no electric washing machines, so women would have to wash their bloody rags and clothes by hand. Disposable sanitary napkins were also cheaper to make and buy, which freed up time and money for women to do other things.1

In 1929, the modern tampon was developed by Dr. Earle Haas, who was inspired by a friend in California after she told him she used a sponge tucked into her vagina to absorb blood.3 Haas started with the idea of using strips of cotton fibers which would be attached to a cord that extended out of the vagina to pull out for removal. These tampons with applicators were first marketed to be an absorbent of menstrual flow. Gertrude Tendrich, who later founded the Tampax brand, bought the patent and tampons hit the market in 1933.4 At this time, menstruation was still very taboo, so in order to buy these feminine products, women covertly placed money into a box at the store instead of buying them in front of the salesperson.3 Even though tampons were taboo, they provided women with a new kind of bodily freedom where they no longer had to deal with metal straps, elastic waistbands, or indiscreet, large pads. With tampons, there is more opportunity for physical activity, and some of the first women who were most eager to try tampons were dancers and swimmers.1 Tampons were also more covert than sanitary napkins, because with some articles of clothing the outline of the pad would show, and considering the long history of women wanting to hide their periods as well as possible, it is not surprising that tampons became widely desired once they hit the market.

However, there were complications when it came to social acceptance of tampon use. Especially in the traditional and value-oriented 1950s, there was concern for unmarried women using tampons due to the idea that it would “break” a female’s hymen. Today, people still try to associate the hymen with virginity, but in the 1950s, a single woman’s virginity was thought to be one of her most valuable assets.1 Worried that using tampons could tear the hymen, many women still only used sanitary belts multiple decades after the tampon was invented. This concern led to the development of “pre-lubed” tampons that were supposed to be easier to insert, and therefore better for sexually inexperienced women.1 In reality, tampons are highly unlikely to tear a woman’s hymen. Hymens also vary widely in shape and type, and the hymen is not a reliable indicator of sexual activity. The hymen can be affected in a variety of ways, from doing the splits to riding a horse, so keep this in mind when considering practices from the 1950s and otherwise.

The 1960s and 1970s brought a lot of revolutionary change for women politically and socially, and these changes also impacted menstrual products. In 1969, Stayfree created the first maxi pad with an adhesive strip, making the belt-style contraption that would keep pads in place obsolete.1 Tampons also increased in popularity, and by 1980, about 70 percent of women were using them.1 Companies at this time tried to innovate to meet market demand, but produced a few products along the way that were unsuccessful. Playtex created a deodorant tampon that was designed to trap blood odor inside the body, but that was unnecessary because blood that is still inside the body is odorless.1 The company Rely also released a tampon made out of polyester that was supposed to be extra absorbent, but the synthetic material was linked to Toxic Shock Syndrome and this caused the products to be recalled.1 Pads and tampons continue to be developed and improved today in order to make them more absorbent, convenient, and reliable to prevent leaking.

Concluding Remarks

Today, companies are innovating rapidly to discover the next best menstrual product. Modern tampons are now made out of cotton fibers that have been pressed together into a cylinder shape so that they can easily be inserted into the vagina. There are different applicators available for tampons, such as the cardboard applicator, plastic applicator, extendable applicator, and the digital, which is applicator free. Modern pads and tampons come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes to fit a range of menstrual flows from light to heavy, and pads are continually getting thinner and more absorbent. Additionally, submarkets now exist for organic and environmentally-friendly alternatives to traditional tampons and pads. There is also growing popularity for new feminine hygiene products, such as the menstrual cup and absorbent period underwear.1

The future of feminine hygiene products will be heavily influenced by new technologies that enter the market, as well as sustainability, because traditional disposable period products have an impact on the environment.5 Ridhi Tariyal and Stephen Gire envision a future where a tampon could do much more than simply absorb one’s menstrual blood; they want to create a tampon that will allow individuals to test themselves at home for infections like chlamydia. Additionally, because menstrual fluids contain much more than just blood, Tariyal and Gire are hoping to be able to diagnose diseases like cancer and endometriosis through this unique tampon blood test. If this new tampon can be tested and sold to the mass market, then women’s healthcare would greatly benefit from the ability to detect life threatening diseases like cancer early.5 As this industry continues to grow, and women’s equality and comfort are being prioritized more, products designed to help women during their period will hopefully continue to improve.

References

- Gabillet, Annie. 2018. “What Did Women Do Before Tampons? A Brief History of Period Products.” Blood + Milk. Retrieved (https://www.bloodandmilk.com/brief-history-of-period-products/).

- Bardis, Panos D. 1967. “Contraception in Ancient Egypt.” Indian Journal of the History of Medicine 12(2).

- Bushak, Lecia. 2016. “A Brief History Of The Menstrual Period.” Medical Daily. Retrieved (http://www.medicaldaily.com/menstrual-period-time-month-history-387252).

- Procter & Gamble. 2014. “History of Tampons and Tampax.” Tampax. Retrieved (https://tampax.com/en-us/about-us/tampax-history).

- Kennedy, Pagan. 2016. “The Tampon of the Future.” The New York Times. Retrieved (https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/03/opinion/sunday/the-tampon-of-the-future.html).

Last Updated: 5 March 2020.