The hymen is a structure within the vulva, which encompasses the female external genitalia. It is a thin piece of mucosal tissue that surrounds and partially covers the vaginal opening (also known as the introitus).1 There is no known biological or evolutionary function of the hymen, but a few hypotheses have been put forward. One theory suggests that the hymen protects the vagina “from contamination by fecal and other materials, especially at the early stage of life.”1

Table of Contents

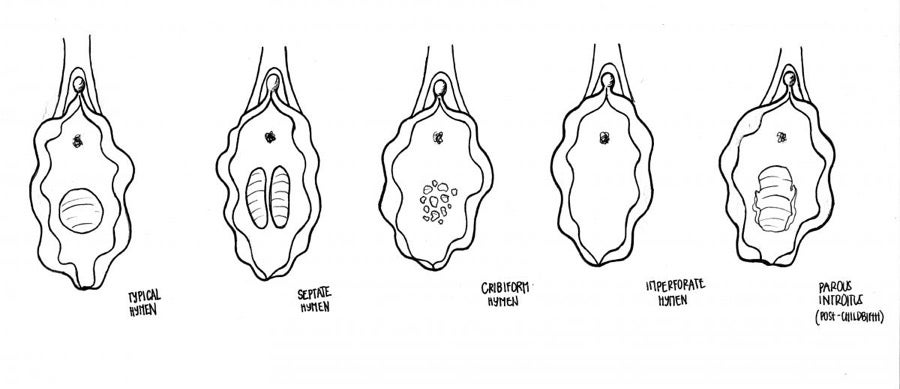

Variations of the Hymen

There is no one right way for the hymen to look. In fact, every hymen is shaped differently; some are thin and have more elasticity, while others are thick and have less elasticity. However, some common configurations have been identified:

- Annular hymen. This ring-shaped hymen has only one opening that perfectly circles the introitus. Sexual activity (whether masturbatory or with a partner) or other physical activity may cause this type of hymen to become wider and less ring-like in shape.

- Septate hymen. A septate hymen has two openings that are separated by a thin band of tissue. Because the hymen tissue can be tough and inelastic, a septate hymen may make it difficult to use tampons and engage in penetrative intercourse.

- Imperforate hymen. An imperforate hymen completely covers the vaginal opening. With this hymen, because there is no way for blood to leave the vagina during menstruation, it may collect and pool in the vagina. This buildup of menstrual blood can be dangerous for a female’s health, so a healthcare professional should be contacted for assistance. Imperforate hymens occur in about one percent of females and may be diagnosed during infancy.

- Microperforate hymen. This is also known as a cribriform hymen. The microperforate hymen covers almost all of a female’s vaginal opening with the exception of a very small hole (or holes). Menstrual blood may be able to leave the vagina with this type of hymen, but only in small amounts. Similar to the septate hymen, females with a microperforate hymen may experience difficulty inserting tampons or engaging in penetrative sex of any kind.

- Parous introitus hymen. This type of hymen is nearly or completely absent and typically occurs in females who have given birth.

Tearing the Hymen

Contrary to what many people think, the hymen does not “break,” nor is penetrative intercourse the only occurrence that can perforate the hymen.2 Instead, the hymen may stretch or tear in certain areas due to a variety of possibilities. These include penetrative sex or masturbation, tampon insertion, or even physical activities such as horseback riding, bicycle riding, or gymnastics, among others. It is not uncommon for females to spot or bleed when the hymen is torn, but this does not always occur. Moreover, he hymen—or parts of it—may remain after a female’s first sexual intercourse or even after childbirth.

A septate, imperforate, or microperforate hymen may be stretched or torn during penetrative sex, tampon insertion, or physical activity. However, if it do not tear or becomes a problem, a healthcare professional may correct it by performing a simple surgery to create a wide enough opening for menstruation to occur. Even if a female has not had penetrative intercourse, she should still be able to menstruate and insert a tampon through an opening in the hymen.

Cultural Significance

Many cultures place value on the hymen as an indicator of a female’s virginity. This belief has been traced back to the medieval era in Europe, as females were expected to be chaste until marriage.1 While this may currently not be a popular belief in many western cultures, an intact hymen is still considered a mark of virginity in many Islamic cultures and is seen as a sign of honor, since premarital sex is disapproved of. Imperforate hymens, although potentially harmful for females, are praised, and surgeries to correct these hymens may be discouraged.1 Females may be subjected to exams by physicians in order to determine whether their hymens are still intact, and are often expected to bleed on their wedding nights due to their hymens tearing.1 If a female is found to not be a virgin by her husband, family, or a physician, she may be beaten or killed. In some cases, her murder may be at the hands of her own husband, brothers, uncles, or father.1

In response to these cultural beliefs and practices, hymen reconstruction surgery (also called hymenoplasty) has become a more prominent method of repairing a torn hymen.1 This surgery is minor and involves suturing a torn hymen in order to create a new hymen. Beyond this, some women insert capsules filled with red dye into their vaginas before their weddings nights in order to make it appear as though their hymens have torn during their first penetrative intercourse. Although neither of these practices are necessarily dangerous to a female’s health, they both reflect and reinforce harmful misconceptions about the hymen and virginity.

The hymen’s relationship to virginity also continues to be emphasized in Western culture. For example, the phrase “pop your cherry” is a term commonly seen in Western mass media (TV, movies, etc.) that refers to the tearing of the hymen and the loss of virginity. So, while Western cultures in many ways seem to be moving away from the idea of the hymen as being representative of virginity, its cultural influence is still apparent.

You can read more about the cultural significance of the hymen here.

Common Myths about the Hymen

Certain myths and misconceptions about the hymen have already been discussed in this article. However, their effects are so prevalent and harmful in many cultures that it is beneficial to state them here:

- All females are born with a hymen. In actuality, some females are born without a hymen or develop such a small amount of hymenal tissue that it appears that they have no hymen.3

- The hymen can only be torn during sexual intercourse. As previously mentioned, having sexual intercourse is not the only way that a female can tear her hymen. While penetrative intercourse is one potential cause of a torn hymen, it may also be torn through daily activities such as exercise or tampon insertion.

- A female will always bleed when first engaging in penetrative sexual intercourse. While some females bleed the first time they have penetrative intercourse, not every female does. This depends on many factors, such as how much hymenal tissue a female has, whether her hymen has already been stretched or torn, or how thick and elastic it is.

- The hymen (whether in-tact, stretched, or torn) is a reliable indicator of virginity. It should be reiterated that the hymen is not a strong indicator of virginity or penetrative intercourse.1 Therefore, the practice that many cultures have of checking a female’s hymen before marriage to make sure she is a virgin is unreliable. A female could very well be a virgin and have no hymen, or she could have had multiple sex partners and still have an intact hymen.

Checking for the Hymen

If you are curious about what your hymen looks like, you can use a flashlight and a mirror to see inside your vaginal canal. Position the mirror in between your legs so you can see your vagina, and slowly spread the “lips” of the vulva (known as the labia minora and labia majora). If you cannot see into your vaginal canal, use a flashlight to illuminate the area (although this can be tricky while trying to hold the mirror and your labium apart). If there is a thin layer of skin with a small hole (or holes) present, your hymen is most likely intact. If you notice small traces of broken skin surrounding your canal, you may have already stretched or torn your hymen. However, there is no need to panic or be scared. Many females are born with perforated hymens. Having a hymen that is already broken or perforated is completely normal and natural.

Concluding Remarks

The hymen remains a highly debated and controversial part of the female body. Its cultural significance as an indicator of virginity has had harmful effects on females from many different cultures. However, it is simply a body part with no clear purpose and no strong predictive qualities of virginity.

References

- Hegazy, A. A., and M. O. Al-Rukban. “Hymen: facts and conceptions.” The Health, 3(4), 2012.

- Cupaiuolo, Christine. “The Hymen: Breaking the Myths.” Our Bodies Our Selves, 2008.

- “Virginity.” Planned Parenthood, n.d.

Last Updated: 20 January 2019.