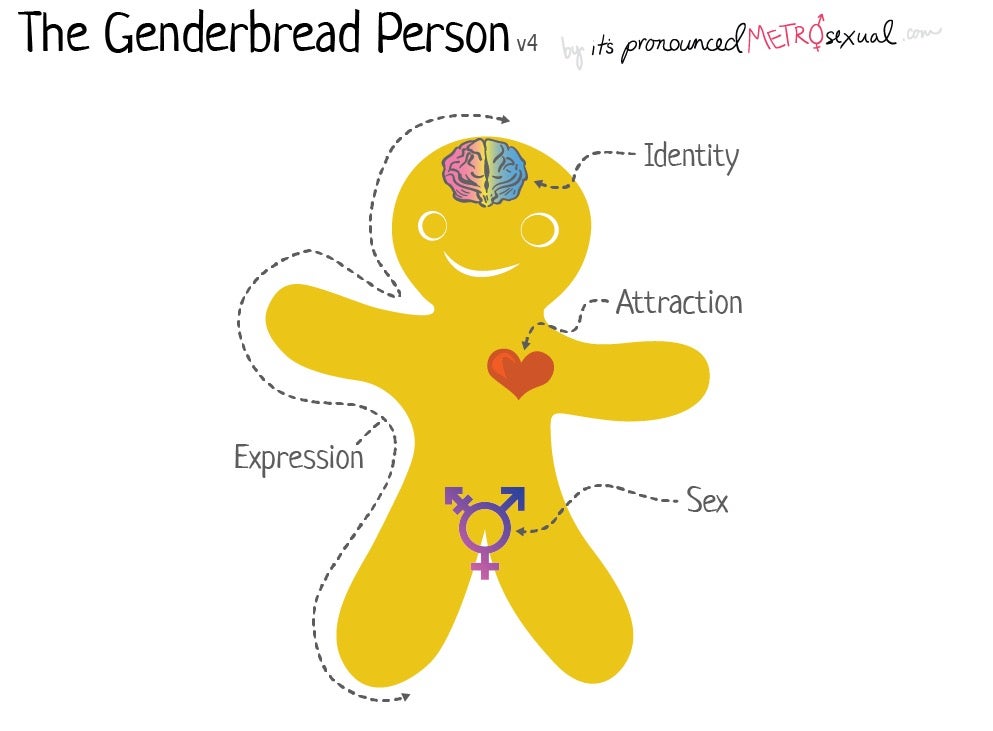

Sex, sexual orientation, gender, and gender identity are commonly confused terms often used inconsistently and interchangeably. However, there are important distinctions between these ideas that involve both biological and social factors. The complex interaction between them influence a person’s identity, sexual attraction, emotional attraction, and gender expression as the iconic image of the “Genderbread Person” illustrates.

Sex vs. Sexual Orientation

Sex and sexual orientation are two distinct concepts. Sex is a term used to describe the biological status of a person. On the other hand, sexual orientation refers to a person’s sexual, romantic, and emotional attraction to other people. A person’s sex does not determine their sexual orientation.

Sex

A person’s sex is determined by chromosomes inherited from their parents. Human beings have 23 pairs of chromosomes in total, and the genetic information on the 23rd pair, referred to as the sex chromosomes, determines a person’s biological sex. Individuals who inherit two X chromosomes will typically develop according to the female pattern, while those who inherit an X and a Y chromosome will typically develop according to the male pattern. The presence of the Y chromosome prompts the development of testes in the fetus. Testes produce testosterone which further stimulates the development of the male internal reproductive system and the development of male external genitalia, including the penis and scrotum.1 Without the presence of a Y chromosome, the female internal reproductive system will typically develop along with female external genitalia, including the clitoris, the outer and inner labia, and the vaginal opening.1 However variations occur in chromosomes and hormones which can lead to discrepancies in the development of the internal reproductive system and external genitalia. Consequently, sexual development is not always binary between the male and female pattern. Intersex refers to situations when there is discordance between a person’s external genitalia and their internal genitalia.2 It is a natural variation in humans, occurring in 0.1 to 2% of the population.2 The sex of a newborn – either male, female or intersex – is usually assigned at birth by a medical professional based on the appearance of the baby’s genitals.3

Sexual Orientation

Sexual orientation describes a person’s preferences for who they find emotionally, romantically, and sexually attractive. A person’s sexual orientation is separate from their biological sex or their gender identity. It is not clear what exactly shapes a person’s sexual orientation, but biological factors and psychological factors have both been theorized. Research has shown that sexual orientation falls on a continuum ranging from exclusively heterosexual (attracted to people of a different sex) to exclusively homosexual (attracted to people of the same sex).4 Bisexuality (attraction to both people of the same sex and another sex) lies along the continuum. Other sexual orientations include pansexuality and asexuality. A pansexual person is sexually, romantically, and emotionally attracted to people regardless of sex or gender identity.5 Some people are asexual, meaning they do not experience sexual attraction, however they can feel emotionally or romantically attracted to others. Asexual individuals often focus their energy on forming emotional bonds, or romantic bonds, instead of exploring further sexual behavior.6 In fact, sexual attraction is distinct from romantic attraction and emotional attraction. Sexual attraction occurs when a person has a desire to explore intimate touching and sexual activity with another individual. On the other hand, romantic attraction is when a person experiences romantic feelings towards another individual, yet sexual activity is not desired. There are different forms of romantic attraction – a person can identify as “heteroromantic,” “biromantic,” or “homoromantic,” which may be distinct from their sexual attraction. Finally, emotional attraction is when a person feels comfortable sharing feelings and having an emotional connection, which can occur within friendships and between family members. For more information on sexual orientations, click here.

Certain sexual orientations are granted privileges in society. For example, heterosexual privilege refers to unearned rights and privileges granted to heterosexual people on the basis of their sexuality. This is due to a commonly held view of heteronormativity, which considers heterosexuality as the “normal” form of sexual expression. Typically, heterosexual individuals are associated with having more privilege in society than homosexuals or bisexuals because heterosexuality fits the gender binary that has been accepted by society. Examples of heterosexual privilege include speaking openly and comfortably about your romantic partner, holding your partner’s hand, expressing affection towards one another in public, and taking your romantic partner to a social event without having second thoughts.7 Heterosexual privilege may cause homosexual and bisexual individuals to believe there is something wrong with them and internalize homophobic attitudes. They may feel intense shame over their sexual orientation or identity, and thus have a difficult time coming to terms with their sexuality. However, sexual orientation is simply another form of human diversity, and all sexual orientations are normal. There are many support groups and organizations designed to help homosexuals and bisexuals overcome any challenges they may experience associated with their sexual identity, such as feeling different, feeling unable to talk about their sexual preferences, and experiencing difficulty finding a community. Membership in a support group has been found to have a positive impact on developing a healthy self identity.8

Gender vs. Gender Identity

Gender and gender identity are also two different concepts. Gender is how society thinks we should act based on gender norms in society. Gender identity is how we perceive ourselves as a male, female, blend of both, or neither. It is a deeply felt conception of oneself.

Gender

Gender refers to the socially constructed ideas and expectations that a culture has about a certain sex. It includes society’s expectations about specific roles and behaviors associated with each sex.9 Multiple studies have shown there are little to no differences between men and women in cognitive abilities, communication, personality traits, measures of well-being, motor skills, and moral reasoning, further proving that gender differences we notice are largely socially constructed.10

Early associations with gender begin at birth with the assignment of sex, which becomes the person’s gender status by default. Gender expression, however, is a continual process that is learned through socialization from families, peers, school, and the media, and in turn, children begin to internalize the social norms and expectations that correlate with their sex. Conforming to gender norms is encouraged in our society, while nonconformity is discouraged and sometimes even punished. Children learn to express themselves as “male” or “female” through choices regarding which clothes, hairstyles, and behaviors they feel most comfortable exhibiting. Consequently, gender is performative – something we “do” rather than who we “are.” However, parents are increasingly raising their children in a more gender neutral manner so children have more agency in choosing their gender identity.

Traditionally, gender has been viewed as binary, either male or female. However, the notion that a person might be in between genders or neither male nor female is becoming more readily accepted in certain parts of the world, such as the United States.

Gender Identity

Gender identity is a person’s perception of their gender. It is independent of their biological sex; rather, it is how a person feels and how they want to present themselves.11 It is not uncommon for a person’s sex and gender identity to be different. A person whose gender and biological sex correlate is considered cisgender. A person whose gender does not align with their biological sex (i.e., an anatomical female identifying with the male gender) is considered to be transgender.9 People who identify as being between genders or a mix of male and female may refer to themselves as genderqueer or gender fluid.6 Individuals who feel they are neither a man nor a woman often refer to themselves as third gender. Some cultures recognize a third gender as part of their gender classifications. For example, in India, Hijra are third gender indivudials who are thought to have spiritual and religious importance and play critical roles in ceremonies and rituals. In addition, many indigenous cultures across the Americas recognize a third gender known as the Two-Spirit or Llamana, who also fulfill traditional ceremonial roles in society.

Cisgender individuals are traditionally seen as having more privilege in today’s society due to their gender identity aligning with society’s expectations of gender. This belief that cisgender is the “correct” form of gender identification has led to cissexism – a concept in the field of gender studies that argues that people in society unconsciously hold prejudices around the idea that identifying as cisgender is “normal” which in turn promotes the gender binary (the idea that there are two distinct genders defined solely by anatomy) and furthers the oppression of non-binary individuals and trans people. Examples of cissexism include using greetings such as “ladies and gentlemen,” not using the correct pronouns when addressing a trans person, or assuming a person’s gender based on their physical characteristics. When negative views towards trans people are expressed openly with the purpose of limiting rights or causing harm, this is referred to as transphobia. Cissexism and transphobia can be very harmful to transgender individuals, leading to possible feelings of deviancy, depression, fear, and isolation.12 Much more needs to be done to combat cissexism and transphobia to get to a point where everyone understands that identifying as transgender is perfectly normal and valid.

Concluding Remarks

The notions of sex, sexual orientation, gender, and gender identity are all important facets of a person’s identity. While these terms are often used interchangeably, there are important differences. Sex refers to a person’s biological sex. Sexual orientation refers to who a person finds sexually attractive as a partner. Gender is a set of societal ideas about a person’s sex, whereas gender identity is a set of personal ideas about one’s own gender. Sexual, emotional, and romantic attraction are all distinct ideas. The complex interaction of these concepts is necessary to understand a person’s sexual, romantic, and personal identities. Regardless of whether or not a person’s gender identity matches up with their sex or with society’s expectations of them, every sexual identity is valid and every person should feel comfortable expressing their true selves.

References

- Brannon, Linda. Gender: Psychological Perspectives, Seventh Edition. Routledge, 2017.

- Griffiths, David Andrew. “Shifting syndromes: Sex chromosome variations and intersex classifications,” Social Studies of Science, 9 February 2018.

- Raveenthiran V. “Neonatal Sex Assignment in Disorders of Sex Development: A Philosophical Introspection.” Journal of neonatal surgery, 6(3), 58, 10 August 2017.

- Savin-Williams, Ritch C. “Sexual Orientation: Categories or Continuum? Commentary on Bailey et al. (2016),” Psychological Science in the Public Interest (PSPI), 25 April 2016.

- Elizabeth, Autumn. “Pansexuality.” The SAGE Encyclopedia of LGBTQ Studies, 2016.

- Yule, M.A., Brotto, L.A. & Gorzalka, B.B. Human Asexuality: What Do We Know About a Lack of Sexual Attraction?. Curr Sex Health Rep 9, 50–56, 1 February 2017.

- “Safe Zone: Privilege,” California State University Long Beach, College of Health and Human Services.

- Poteat, V.P., Calzo, J.P. & Yoshikawa, H. “Promoting Youth Agency Through Dimensions of Gay–Straight Alliance Involvement and Conditions that Maximize Associations.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 45, 1438–145, 18 Jan 2016.

- “LGBT Terms and Definitions.” Spectrum Center University of Michigan, 12 Nov. 2016.

- Johnson, Stefanie. “What the Science Actually Says About Gender Gaps in the Workplace.” Harvard Business Publishing. 17 August 2017.

- “Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Definitions.” Human Rights Campaign, n.d. Web. 29 January 2015.

- “What’s Transphobia?” Planned Parenthood Federation of America. 2021.

Last updated: 3 March 2021.