In recent decades, development of reliable and reversible methods of female contraception greatly expanded family planning options available to females. Male contraceptive development, however, has been greatly overlooked.

Currently, male condoms and vasectomies are the only forms of reliable male contraception effective at preventing pregnancy for a female partner (and, in the case of latex and polyurethane condoms, preventing the transmission of sexually transmitted infections). Despite this, condoms and vasectomies are limited in comparison to the effectiveness, variety, and availability of female contraceptive options. Though immediately reversible and inexpensive, condoms have higher failure rates than most female contraceptives and serve only as a short-term birth control option that must be used independently every time the user has sex. Vasectomies, on the other hand, are highly effective but not always reversible or easily accessible.

Considering that the global rate of unintended pregnancy is 40% and one third of sexually active couples rely on contraceptive methods requiring male participation for family planning, there is a clear unmet need for development of reliable, reversible, long term birth control options for males.1

This article focuses on the innovative developments in male contraception research that could be made available to the general public in the next few years, existing forms of sexually transmitted infection (STI) protection and contraception for males, and the political dynamics surrounding the development of these new male birth control options.

Factors Affecting the Development of Male Birth Control

Enthusiasm of potential users, lack of involvement from the private sector, nonprofit funding and advocacy, and challenges presented by the biological processes of the male reproductive system have shaped the history of male birth control research and continue to have positive and negative effects on the development of increased contraceptive options for males today.

Attitudes Towards Male Contraception

Despite the lack of options for male birth control currently available on the market, many males and females are in favor of the development of male contraceptives. A population-representative survey of 9,342 men between the ages of 18-50 across nine countries concluded that an average of 55% of men are willing to use new hypothetical male contraceptives.1 Females in stable relationships with males are most likely to have interest in the development of male contraceptives and to trust that their male partner will use it effectively.2 These results are consistent across cultural and socio-economic settings and demonstrate a widespread demand for the development of male contraception.1

Biological Complications

While interest in the development of male contraceptives is strong, the logistics of suppressing sperm production to render males temporarily infertile are more difficult than suppressing the female reproductive cycle. Where female contraceptives only need to prevent the fertilization of a single ovum cell once a month, male contraceptives need to effectively work against the 15-200 million sperm cells per mL of ejaculate to ensure temporary infertility in males.2 In other words, the numbers game is much larger for male contraception, which increases challenges for researchers trying to perfect delivery and function in male contraceptive development.

Cost-Benefit Tradeoffs in Decision Making

Historically, the incentive to produce male contraceptives has been overshadowed by stronger advocacy for female contraception. This is due to differences in the risk-reward decision process between males and females taking contraceptives.2 When females evaluate the decision to take a contraceptive, they weigh the potential side effects of the hormonal contraceptive against the health risk of becoming pregnant as well as all responsibilities that follow. While males must similarly evaluate the cost of contraceptive side-effects, they do not run the direct health risk of becoming pregnant themselves. This is one reason why urgency and advocacy for contraception previously focused on female-specific birth control and neglected further research for male-specific birth controls beyond condoms and vasectomies.

Funding and Advocacy

One significant reason why a greater variety of male birth controls are not as available as female contraceptives is rooted in the reduced commercial and private industry support for the development of male contraception.3 Big pharmaceutical companies are reluctant to fund research and production of male contraceptives due to the unclear guidelines and requirements needed for approval of effective male contraceptives and perceived lack of profitability of male contraceptives.3 The development of new male birth control is an expensive endeavor and, even if the research shows success, the production of male contraceptives is disfavored due to the idea that it will undercut profits made from developed female contraceptives that cost less to produce.1

Despite the lack of private sector involvement, research on effective male contraception is being pushed forward by government, academic, and non-profit organizations.3 The World Health Organization (WHO), the Contraceptive Research and Development Program, the Population Counsel, and the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) are the main research leaders in the field of male birth control.3 Groups like the International Consortium of Male Contraception also contribute as political advocates promoting cooperation between researchers, government, industry, and private companies to increase development and availability of male contraception.3

Types of Male Birth Control in Development

The overall goal of male birth control is to reduce male sperm count to a level that greatly decreases the likelihood of pregnancy in female partners. Please note, however, that the following developments only function to reduce male fertility and do not provide essential protection against sexually transmitted infection (STIs).

The following are ways that male birth control may work to prevent chances of pregnancy in females:

- Reducing sperm production entirely (hormonal contraceptives)

- Preventing sperm from properly functioning (non-hormonal drugs) by impairing:

- Sperm motility

- Ability of the sperm to fertilize the female’s egg

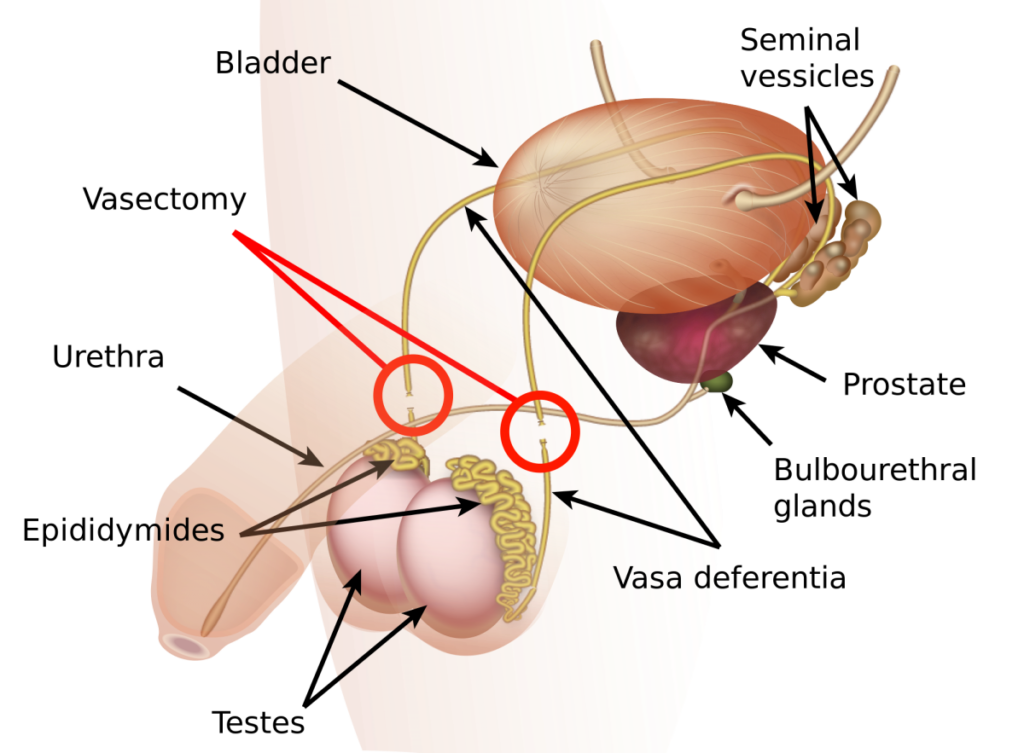

- Blocking sperm transport (condoms or vaso-occlusive methods) out of the vas deferens during ejaculation.

Ideally, a new male birth control will have the following attributes:

- The ability to prevent pregnancy at a rate comparable to female contraceptives available

- Minimal side-effects on libido, mood, sexual activity

- Uncomplicated usage requirements

- Rapid effectiveness

- Reversibility

- A single-agent design (all needed components are in the same pill or single gel)

- The ability to be used independently of each individual sexual act,: effective long-term prevention (e.g. birth control pills or implants)

- No effects on potential offspring or fertility

To reach the standards needed to be put on the market, researchers are working to improve their new birth control options to maximize all of the categories listed. Innovative new forms of hormonal and nonhormonal male contraception already have been shown to demonstrate several of these characteristics; hormonal contraception in particular is excelling in clinical trials that are currently underway and the closest of the methods to reaching the market first.

Hormonal Contraception

Testosterone is a key sex hormone, or androgen, with a crucial role in fertile sperm production (spermatogenesis).2 Consequently, most research involving male hormonal contraception seeks to manipulate testosterone levels in combination with of other naturally occurring hormones like progestins.2

Normally, male sperm production is constantly occurring after puberty and is regulated by a complex hormonal chain of command that starts with signaling from Gonadotropin-release hormone (GnRH) in the brain.2 GnRH signals for increased production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH).2 Carrying the message down the hormonal chain of command from the brain to the male reproductive organs, LH provokes the synthesis and secretion of testosterone and FSH supports the maturation of sperm cells in the testes. Testosterone functioning in the testes is essential for normal production of fertile sperm in males.4 The entire process of sperm maturation takes approximately 72 days to complete.4

Androgens, like testosterone, formed the foundational strategy for hormonal contraceptives, which were first tested in the 1990s by the landmark WHO trails, performed on 617 men in 10 different countries.1

These early trials used androgens alone to reduce sperm production in the testes to reliably prevent fertilization and likelihood of pregnancy in a female partner. The benchmark for this new contraceptive’s effectiveness in suppressing male fertility is based on sperm count. The average concentration of sperm in a healthy male’s ejaculate is 12-120 million sperm per milliliter.4 A contraceptive was determined to be 97% effective in preventing chances of pregnancy in a female when the sperm count was less than 1 million sperm cells per milliliter of ejaculate.4 Complete absence of sperm in the ejaculate was defined as azoospermia. Fertilization and impregnation of a female partner is impossible in azoospermic males.4

The administration of testosterone as a male hormonal birth control increased levels of androgens (testosterone) circulating in the bloodstream rather than being concentrated in the testes. Testosterone circulating in the brain was able to shut down GnRH signaling in the brain and thereby reduce production of sperm in the testes to azoospermic levels in several participants.

Phases 1 and 2 of the early WHO studies were revolutionary for male contraception because their results demonstrated that androgens could effectively suppress spermatogenesis in males to levels comparable to female hormonal birth control that were also reversible when treatment ceased.3 Among 617 males studied in 10 international sites, 96% of the participants had sperm counts that were less than 1 million sperm/mL, demonstrating equivalent effectiveness between this male treatment and available female hormonal birth control.1

However, some problematic side effects resulted from the high concentrations of testosterone circulating in the male participant’s bodies, outside of the intended target site of spermatogenesis in the testes. Some of the androgenic side effects included mood changes, increases or decreases in libido, self-reported acne, weight gain, issues with cholesterol, and some concern with frequency of moderate to severe depression.2 To minimize some of these androgenic effects, researchers reduced the dosage of testosterone in potential male hormonal birth control by adding progestin.5 Pairing testosterone treatments with progestin reduced androgenic side effects, maintained the effectiveness of the contraceptive, and improved the overall safety of the treatment.5

Three types of male hormonal contraception (listed below) are currently in clinical trials and are the most likely of all the forms of male birth control in development to enter the market first.6 The goal of this research is to produce a reversible contraceptive for males that minimizes androgenic side-effects, functions as a single agent product (simultaneously using androgenic and progestin activity in the same dose), and has comparable effectiveness to female contraception in preventing pregnancy.

Dimethandrolone Undecanoate (DMAU)

Currently in clinical trials, Dimethandrolone Undecanoate (DMAU) has the potential to be the male equivalent to the female birth control pill.2 It can be administered as a daily oral pill or as an injectable form of contraception. In both cases, DMAU acts as the ideal single-agent, containing both androgen and progestin activity to reduce sperm production in males to the acceptable <1 million sperm/mL ejaculate or to azoospermic (no sperm in the ejaculate) levels.2 Trials for the daily oral pill so far have shown DMAU to suppress male sex hormones to levels consistent with effective contraception without any objective changes in mood or sexual function of the males receiving the treatment.

Nesterone + T-gel

The combination of Nesterone, a pure progestin gel, and T-gel, androgenic testosterone gel, is also currently being tested in clinical trials.6 A daily application of a combo gel containing both Nesterone and T-gel to the skin resulted in 88% effective spermatogenesis suppression in a small preliminary trial designed to assess potential of the combination gel for further development.2 Based on this, a current trial involving 400 couples across four continents is rigorously testing the effectiveness of this combo topical gel as a potential male birth control.5 Results are expected in 2021.5 Due to the ease of application, the Nesterone T-gel combo contraceptive showed higher rates of acceptance amongst males than injections.2

Injectable Contraception: NET-EN and TU

The combination of injectable NET-EN (norethisterone ethanoate) hormones and TU (testosterone undecanoate) provides another means of altering male hormonal levels and temporarily suppressing male fertility.2 Both NET-EN and TU are injectable, long-lasting hormones that have proven to be effective contraceptives in previous studies.2

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently examined the effectiveness of a single injection containing both NET-EN and TU in an international trial conducted at 10 different study sites.2 As a single-acting agent (delivering both hormones at once), this approach to hormonal birth control injections increases the ease of use for the potential contraceptive.5 The study showed a high rate of success comparable to the effectiveness of female hormonal contraceptives.7 Spermatogenesis was suppressed effectively within 26 weeks and continued injections over 56 weeks maintained the temporary infertility of male subjects.7 Recovery of fertility was also shown one year after the trial had ended.7 More than 75% of the male participants were satisfied with the effectiveness of the treatment and were willing use the combo NET-EN and TU injections if it was made widely available.7

Though clinical trials have demonstrated that modern, easy-use, fully reversible and effective hormonal birth controls for males will be available in the near future, the majority of these trials are still testing the effectiveness of the birth control (Phase 2 of clinical trials).8 Before the contraceptives can be marketed to the general public, they will have to pass Phase 3 of clinical trials, which involves randomized testing on hundreds to thousands of consenting participants.8 Nevertheless, hormonal male birth control has the potential to drastically improve males’ ability to actively contribute in family planning in addition to traditional contraceptive methods, such as condom use.

Non-Hormonal Birth Control

Though not as developed nor close to market availability as hormonal contraceptives, non-hormonal birth controls also provide effective methods of pregnancy prevention. Many of these non-hormonal contraceptives interrupt sperm maturation processes in the testes to prevent production of fertile sperm, to block the path of fertile sperm from joining the ejaculate, or to prevent the sperm from properly interacting in the fertilization event if it reaches the ovum, which also prevents pregnancy in a female partner.4

Vaso-Occlusive Techniques

Vaso-occlusive methods of male contraception use polymers to reversibly block the passage of the sperm out of the vas deferens using safe polymer, the thin tube enabling transport of the sperm out of the testes.2 When using this birth control, males will still ejaculate at orgasm, but there will be no fertile sperm capable of causing pregnancy in a female in the male’s semen.

Reversible Inhibition of Sperm Under Guidance (RISUG)

Since the 1980s, researchers in India have been working on reversibly preventing sperm from exiting the vas deferens using a nontoxic polymer called Reversible Inhibition of Sperm Under Guidance (RISUG).9 Animal studies have shown that the RISUG procedure can be reversed to restore fertility in treated mice with a second injection of dimethyl sulfoxide that flushes out the RISUG gel.2 The procedure only takes about 15 minutes and is minimally invasive, effective almost immediately, and predicted to be affordably priced.9

Small clinical trials in India have shown that this procedure renders males temporarily azoospermic and prevents pregnancy for a year following the RISUG injection into both vas deferens.4 Despite this, there has been little research conducted concerning the long-term effects of this contraceptive method on males or their potential future offspring, so large scale clinical trials are needed to assess whether or not the injection has any adverse side effects and the extent to which fertility is restored in human males compared to the effectiveness shown in animals models.2

Vasalgel

Although similar in concept, Vasalgel is different than RISUG. They are both gel polymers that are injected into the vas deferens and block the passage of sperm; however, Vasalgel is formulated differently to better adhere to FDA guidelines in the USA in hopes that it will pass government health regulations and be readily available on the market.10 The goal of Vasalgel is to be a fully reversible, durable, and effective method to prevent ejaculation of viable sperm. In studies conducted on rabbits, sperm flow was restored after a sodium bicarbonate solution was injected into the vas deferens to flush out the gel.10 A 2017 study using adult male rhesus monkeys confirmed Vasalgel’s effectiveness as a form of male contraception in primates.10 Vasalgel still needs to successfully complete human clinical trials and gain regulatory approval to be marketed to the general public in the future.10

Small Molecule Contraceptive Precursors

Rather than physically blocking the sperm, other promising forms of non-hormonal birth control in early stages of research use small molecules delivered orally in pills or injections to impede normal sperm development.6 For instance, Catsper Binders and Eppin molecules block sperm’s ability to effectively swim to the ovum, preventing fertilization if developed into an effective and safe contraceptive drug.6 Other molecular compounds alter the development of the fertile sperm in the testes.6 Researchers are also interested in exploiting the role of retinoic acid, a metabolite of vitamin A, that is essential in healthy sperm production.6 Use of Retinoic Acid Antagonists in future male contraception could target this role and essentially kill the function of retinoic acid in sperm production, resulting in temporary infertility.2 Despite these exciting applications, the majority of these molecular compounds are in preliminary stages of research and will not be seen on the market for male birth control for some time.

Currently Available Options for Male Birth Control

Though the new developments in hormonal and nonhormonal birth control are exciting, these methods will still need to be used with condoms once available on the market to prevent STI transmission in addition to pregnancy. Currently, condoms and vasectomies are the only options for male birth control on the market.

Condoms are one of the only forms of contraception effective at preventing both pregnancy and STI transmission. Around the world, 50 million couples rely on condoms for contraception.1 While condoms do have a higher typical use failure rate (13%) than many female birth control options available, this is usually due to incorrect use.2 When used properly, condoms are 98% percent effective at preventing pregnancies.11

Condoms are one-time use forms of contraception; a new condom must be used with every new sexual act. This can contribute to incorrect perceptions that condoms inhibit sexual spontaneity and pleasure.1 In some cases, reduced sensitivity while wearing a condom may be due to insufficient lubrication, which can be resolved by incorporating water-based lubes (which won’t degrade latex condoms) in sexual activities.11 Males can increase sensation during sex while using condoms by putting a drop or two of lubricant inside the condom before it is unrolled – be careful though, since the addition of too much lube could cause the condom to slip during sex.11

Since there is such a large variety of male condoms available, individuals can experiment with different options to find a condom that feels best. Similarly, condom-use can be incorporated into sexual foreplay to mitigate concerns about reduced sexual spontaneity.11 Many people report that sex with condoms reduces their worries about unintended pregnancy and STI transmission, allowing them to better enjoy their sexual experiences and promoting more spontaneity.11 Benefits of condoms include the following:

- Only form of contraception that prevents STI transmission

- Widely available and reliable form of male contraception

- Affordable

- No side-effects

- Immediately reversible

Whereas condoms are accessible, cheap, and do not interfere with long-term male fertility, vasectomies are more effective than condoms with a failure rate of less than 1%.4 However, as a surgical procedure, a vasectomy can be costly, have limited accessibility as contraceptive option for males worldwide, and have poor rates of reversion, since 20-30% of males remain infertile following the vasectomy reversal procedure.4 Vasectomies are a great birth control option for males who are certain that they do not want offspring and have access to the procedure.

Concluding Remarks

Exciting and long-anticipated, new developments in male birth control, including a “male pill,” hormone injections, vaso-occlusive techniques, and combination gels, are currently in clinical trials and may be available to the general public in the near future. An expansion in the variety of male contraceptive options will allow males to be more actively involved in family planning worldwide and generates more agency for males to choose the birth control that is right for them. Though these developments are highly promising, all of the methods listed in this article only protect against pregnancy, not STIs. Once on the market, these male contraceptives should be used in combination with condoms to ensure protection from STI transmission while also enabling greater control over male reproductive capacity with these new birth control methods.

References

- Amory, John K. “Male Contraception.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 106, no. 6, Nov. 2016, pp. 1303–09. Crossref.

- Behre, Hermann M., et al. “Efficacy and Safety of an Injectable Combination Hormonal Contraceptive for Men.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 101, no. 12, Dec. 2016, pp. 4779–88. Crossref.

- Colagross-Schouten, Angela, et al. “The Contraceptive Efficacy of Intravas Injection of Vasalgel™ for Adult Male Rhesus Monkeys.” Basic and Clinical Andrology, BioMed Central, 7 Feb. 2017.

- Gava, Giulia, and Maria Cristina Meriggiola. “Update on Male Hormonal Contraception.” Therapeutic Advances in Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 10, Jan. 2019, p. 2042018819834846. SAGE Journals.

- Handelsman, David J. “Male Contraception.” Endotext, edited by Kenneth R. Feingold et al., MDText.com, Inc., 2000. PubMed.

- Long, Jill E., et al. “Male Contraceptive Development: Update on Novel Hormonal and Nonhormonal Methods.” Clinical Chemistry, vol. 65, no. 1, Jan. 2019, pp. 153–60. PubMed.

- “Overview of Clinical Trials.” CenterWatch, Centerwatch.

- Thirumalai, Arthi, and Stephanie T. Page. “Recent Developments in Male Contraception.” Drugs, vol. 79, no. 1, Jan. 2019, pp. 11–20.

- “Types of Male Birth Control in Development: Male Contraceptive Initiative.” Male Contraceptive Initiative, Male Contraceptive Intiative 2019, Mar. 2018.

- Young, Rob D. “Myths and Facts about… Male Condoms.” IPPF, International Planned Parenthood Foundation, 11 Mar. 2019.

- Wang, C., et al. “It Is Time for New Male Contraceptives!” Andrology, vol. 4, no. 5, 2016, pp. 773–75. Wiley Online Library.

Last Updated: 21 May 2019.