Opinions regarding what constitutes an effective and appropriate sex education vary between countries, nations, cultures, and even among families. The sex education curriculum of any given society typically reflects the dominant cultural values and norms of the greater community. There has yet to be a nation today to achieve comprehensive standards. In past decades, “abstinence-only” sex education programs dominated much of the United States due to funding incentives from conservative political groups; remnants of their influence can still be seen in American legislation today.1

Exhaustive scientific and sociological research during and after the 2004 Bush administration has proven that abstinence-only programs have little or no effect on teenage sexual behavior in terms of deterring sexual activity. A majority of these conservative programs, including the “Just Say No” campaign and various other virginity-pledge-based campaigns, stress that abstinence is the only safe and moral strategy to avoid teen pregnancy and STIs (Sexually Transmitted Infections). On the other hand, comprehensive programs (which include information on topics like condoms, contraceptives, STIs, anatomy, sexual functioning, communication skills, etc.) actually cause teens to delay sexual activity and be more likely to use methods of birth control when and if they do become sexually active.1

A Recent History

Between 1998 and 2003, the United States government spent at least 899 million dollars to support abstinence-only sexual education programs (even after research proved their inefficacy at preventing teen sexual activity and pregnancy) on the premise that “values trump data.” After the results of at least 50 evaluations were released, professionals concluded that financial support for these programs was a gross misuse of federal, state, and local funds. In 2008, when the composition of Congress changed (and the majority perspective was less conservative), funds for abstinence-only programs were terminated by the Obama administration, and 114 million dollars were allocated for effective, evidence-based teen pregnancy prevention programs by the following year.2

Although the media may periodically suggest strong resistance to comprehensive sexuality education, surveys show that there is actually overwhelming support for adolescent sex education in the United States when students are at least twelve years old or older. A nationally representative sample in 2003 indicated that 93% of parents of seventh and eighth grade students said it was “important” or “very important” that sexuality education be part of school curriculum. In the same year, a study done by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 88% of parents of children in middle school agreed that having a sex education program in school made it easier for them to speak with their children at home about sex.2 Some parents find it difficult to discuss sexuality with their children because they are embarrassed or do not know enough information to inform their children explicitly or effectively.2

Comprehensive sexuality education in schools can effectively facilitate parent-child conversations about sex and allow both parents and students to feel more comfortable exchanging information and expressing their questions and concerns. Sex education in school should not be considered an alternative to talking with your child about sex, but instead an academic introduction and supplement to the information you provide.

Public Versus Private Issue

The proper setting for children to learn about sexuality has been a controversial debate for many years. Opposing groups argue whether it is either the responsibility of parents and guardians, or the responsibility of the public school system to properly educate children on vital information regarding sexuality. In contemporary American society, sexuality is still primarily considered to be a “private” topic. Many believe that speaking with children about sexuality promotes early and increased engagement in sexual activity and promiscuity (although research suggests otherwise). Some parents prefer to teach their children about sexuality from an angle that accentuates their personal beliefs and values, while others prefer to avoid the conversation entirely. Either way, correct and accurate information is invaluable when it comes to the education of children in all aspects of human health. Because education on human sexuality is not guaranteed in the home, the responsibility falls on the public to inform its students about their health and well-being.2

The Opposition is a Minority

Some American citizens (typically religious conservatives) remain against educating children about sex in the public school system. They may feel that, amongst other reasons, abstinence until marriage is morally imperative (although only 5% of Americans actually remain sexually abstinent until marriage), and it is ultimately a parent’s responsibility to educate their child about sex if they choose to do so. Parents and other adults may also believe that no matter the content, sex education programs will legitimize and promote sexual activity among teens and facilitate the associated negative consequences, despite the plethora of studies disproving this hypothesis.2 Although stories covered in the media may typically portray favoritism towards abstinence only sex education programs by certain religious affiliations, parents and educators must remember that such perspectives are not very common. These views are generally voiced and portrayed in the media because conservative advocates express their views on various platforms for increased exposure.

Furthermore, those who are against comprehensive sex education may be overlooking the realistic, unpredictable alternative to an accurate, information-based education: skewed information from the media. A study done in 2001 indicated that teens 13 to 15 years of age receive over half of their information about sex from friends, television, movies, and other entertainment sources. Information on sexuality from such sources is often sensationalized and unrealistic. Many sex educators regard the exchange of such information between adolescents as “the blind leading the blind” because youth often have unknowingly inaccurate or unrealistic information that they then pass on to one another. Furthermore, the sexual misinformation that circulated in 2001 was likely incomparable to the large amount of non-credible sources teens now have access to in an era heavily influenced by technology and entertainment media.2 In fact, according to a recent study, many teens report that they would like to have a comprehensive sexual health and education course.2

Where We Are Now

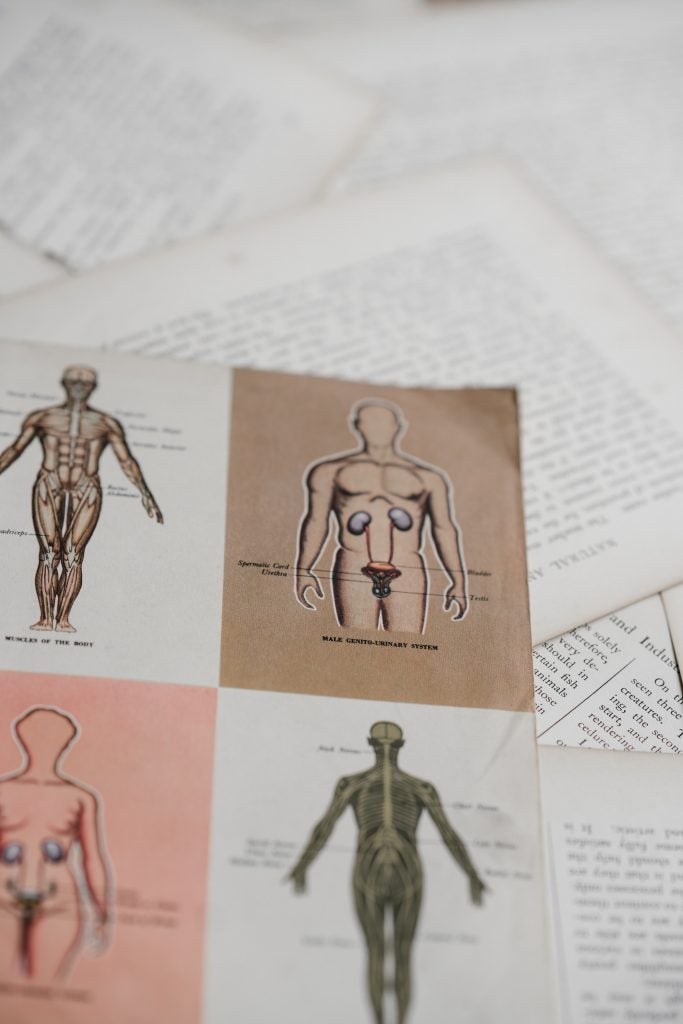

New programs aim to be both comprehensive and scientifically based. Such programs discuss social aspects of biological changes, sexual aspects of reproduction, reproductive anatomy and physiology, puberty, reproduction, body image, and sexual orientation. Many courses often do not consider the pressure and social stigma that comes with having or not having sex with any given partner.2 The severity of these factors depend on the person’s age, sexual orientation, culture, and much more. The implementation of the social learning theory into sexuality courses is crucial as it brings an interdisciplinary aspect to sexual health and education.2

Over the past several years, there has been a sharp increase in teen pregnancy rates, prevalence of STIs among young adults, and HIV infections in adolescents. However, there are several aspects of effective sexual education programs that reduce the introduction to and frequency of reckless intercourse. The CDC has identified that such programs focus on reducing risk-taking behavior by incorporating theories of social learning, using personalized curriculum to address their audience, discussing the media and social pressures that encourage risky behavior, reinforcing clear values, and stressing communication skills. Creating and implementing effective programs is cost effective in the long run. If less students participate in unprotected sex, then there will be less need to treat STIs, HIV infections, and unintended pregnancies.2

If these significant risks associated with teen parenting are not enough to highlight the importance of comprehensive sex education standards, a finding by the National Conference of State Legislatures stresses the overall financial loses to our nation: teen childbearing in the U.S. costs taxpayers at least $10.9 billion annually for the public assistance needs of these mothers. Additionally, treating young people with sexually transmitted infections costs taxpayers approximately $6.5 billion annually (not including the costs associated with treating HIV/AIDS). Thus, our nation spends almost $17.5 billion annually on treating the consequences of withholding information from our young people that could possibly prepare them for healthy and fulfilling adult lives and protect them from disease and inevitable confusion.3

Where to Go from Here

Here at SexInfo, we believe that people of all ages have the right to know about their bodies and how to protect them. It is unfortunate that such an important aspect of human existence is often spoken of as “dirty” or “inappropriate” and that there has been an enormous taboo placed on the discussion of sex-related topics with children. It is not guaranteed that, aside from euphemisms, innuendos, and dirty jokes, a child will ever acquire effective language to discuss sex-related topics or obtain the accurate information they are seeking (or are simply curious about) until early adulthood. Giving children a formal, age-appropriate education beginning in primary school will equip them with the knowledge and skills they need to make informed and responsible choices as they mature.

Additionally, it is important that parents and educators use any opportunities they may encounter to facilitate continuous conversations with young people about sex, as opposed to one “big talk”. Frequency of discussion will increase the level of comfort among children and students, allowing them to freely express their questions and concerns openly and honestly. Furthermore, teaching a positive view of human sexuality helps foster young people to eventually experience happy and healthy intimate relationships. Supplying them with the proper language to discuss issues they may face is essential for personal safety, success, and later communication with sexual and intimate partners.

Because comprehensive sex education prepares students for both the positive and potentially negative consequences of becoming sexually active, most sex educators recommend that any sex education curriculum be medically accurate and age appropriate. The following are guidelines as recommended by the Sexuality Education and Information Council of the United States (SEICUS) for comprehensive sexuality education. SIECUS recommends that human development, relationships, personal skills, sexual behavior, sexual health, and society and culture should be taught at all age levels with increasing depth across grade levels.3

There remains a debate regarding the availability of condoms for students at school campuses and even some clinics. Although the majority of parents want their children to use condoms if they are sexually active, they would also like to have the ability to restrict such access as well. The greatest opposition to condom availability is posed by the Roman Catholic Church, which opposes all forms of contraception. Others may believe that condoms reinforce and encourage young adults to become hyper-sexual or have sex outside of marriage, which they view as a risk that leads to unplanned pregnancies. However, evidence asserts that students with greater accessibility to condoms have a “reduction in the incidence and frequency of sexual intercourse.”2

Until comprehensive standards for sex education are reached across the world, there are a few things we believe are essential for students to learn either from their parents or teachers. Children who have not yet experienced puberty should know the basics of their anatomy, how their bodies work, how babies are conceived, and what they should expect of their bodies in the near future (during puberty). If children will not be receiving sex education courses in their early teen years, they should be exposed to other aspects of sexuality, such as love and relationships, contraception, sexual violence information (such as sexual assault and domestic abuse), and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in primary school. If children will be receiving additional sex education in their early teen years, then some of these advanced subjects (like contraception and STIs) can be left for a later time as they are more likely to face these issues after puberty. If such advanced topics are never presented in a child’s formal education, parents must introduce these topics at a time they deem appropriate.

When teaching sex education, a teacher should always give accurate information, clarify misunderstandings, relate material to students’ lives, and be approachable. If a teacher is embarrassed to talk about certain issues, children may perceive the subject as being taboo. Therefore, a teacher should make sure that he or she feels comfortable talking with children about all aspects of sex education, and be prepared to answer any questions his or her students may have. Sometimes children may feel uncomfortable about asking questions during class, so many teachers have their students write anonymous questions on a piece of paper, fold them up, and pass them in so the teacher can draw from the papers at random. This gives children a chance to ask important questions, while also letting the teacher know what their students are curious about. Also, consider using visual aids, when appropriate, so the children can see pictures of the topics being discussed.

Concluding Remarks

A good teacher is a good listener who is able to gauge what students know and want to learn based off of the questions they ask. In order to be successful, an educator must also keep in mind the cultural differences their students may have, and how their families’ values might shape their beliefs. A teacher may want to discuss with parents and other adults what they think should be taught in class, keeping in mind local laws regarding sex education. Ultimately, any sexuality education given to students must be accurate and leave children with an awareness of their bodies and how to protect them.

References

- LeVay, Simon, Janice Baldwin, and John Baldwin. Discovering Human Sexuality. Sinauer Associates, Inc., 2009.

- Hyde, Janet and John D. Delamater. Understanding Human Sexuality, 11th Ed. McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2011.

- “Lesson Plans”. SexEd Library.

Last Updated: 30 January 2018.