HIV, or Human Immunodeficiency Virus, is a sexually transmitted virus that, if left untreated, can progress to AIDS. AIDS stands for Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, and is the symptomatic part of this infection. Because HIV is a “retrovirus,” each virus is encased in a protein shell, which allows them to attack and alter cells from the host cell’s DNA. Once HIV is in the blood stream, it targets specific cells that are very important to the immune system’s ability to fight off infection, such as CD4 cells (T cells). HIV then hijacks these cells and uses them to create HIV-positive DNA. Over time, so many of these cells are attacked that an infected person is unable to fight off infections and disease. This depressed immune system is the direct precursor to AIDS, during which opportunistic infections that would not normally be life threatening become extremely dangerous, and often cause HIV/AIDS-related deaths.1

Table of Contents

Where Did HIV Come From?

Currently, a group of scientists have identified a species of chimpanzee in Central Africa as the source of HIV infection in humans. They believe that the simian immunodeficiency virus, or SIV, was the chimpanzee version of the virus, and was likely transmitted to humans and mutated into HIV when people hunted these chimpanzees for meat subsequently coming into contact with the infected blood. Further studies report that HIV may have jumped from apes to humans as far back as the 1800s. Over time, the virus slowly spread across the rest of the world, reaching parts of North America during the mid-to-late 1970s.1

Transmission/Pathology of HIV and AIDS

HIV can be present in blood, semen, vaginal fluids, saliva, urine, and breast milk although the concentration and likelihood of contraction varies for each of these bodily fluids. The virus is most commonly transmitted through the exchange of blood and semen, since these two fluids contain the highest concentration of the virus. Once the virus infects the body, HIV attacks the CD4 lymphocytes, or T-cells, in the blood. T-cells are central to the part of the immune system that guards against illnesses. A healthy person has a T-cell count between 800 and 1,200 CD+ T-cells per cubic millimeter (mm3) of blood; meanwhile, a person with HIV has only around 500 CD+ T-cells per cubic millimeter (mm3) of blood.1

Symptoms and Stages of HIV

If an infected person contracts HIV and does not receive treatment, they will generally progress through three stages of the disease.

Stage 1: Acute HIV Infection

This first stage starts within 2 to 4 weeks of infection, and while it is progressing a person may experience flu-like symptoms. These may include swelling of the lymph glands, fatigue, weight loss, night sweats, etc. This is simply the body’s natural response to infection, and during this stage is when the infected person is most contagious, as they have large concentrations of the virus in their blood. Some people may not experience symptoms at all, which is why it is important to get tested immediately even if there is only a slight chance you were been exposed.2

Stage 2: Clinical Latency

This stage is sometimes called asymptomatic HIV infection, or chronic HIV infection. At this time, the virus is still active in the body, but it reproduces at extremely low levels. For people who are not actively treating their infection, this stage can last a decade or more, while some may progress a little faster. Those who are being treated may be in this stage for several decades. This is due to “viral suppression,” a direct result of taking anti-viral cocktails. It is important to note that people who are infected can still transmit HIV, even though they are much less infectious than someone in the acute stages of infection. During this period, the virus may be progressing very slowly throughout the body, attacking and altering host cells to produce HIV-positive DNA. Generally, at the end of this phase, an infected person’s viral count (amount of virus in the body) begins to rise and the amount of CD4 cells (T cells) begins to fall as the body becomes less and less able to fight off infections. At this time, the person may begin to experience symptoms as the disease progresses to stage 3.2

Stage 3: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

This stage is the final and most severe stage of HIV infection, and it is usually diagnosed when the CD4 cell count drops below 200 cells/mm. At this point, the immune system is badly damaged, leaving an infected person dangerously susceptible to an increasing number of severe medical conditions, known as opportunistic illnesses. Without treatment, people with AIDS generally survive about 3 years. Symptoms of AIDS include chills, night sweats, rapid weight loss, sores of the mouth/anus/genitals, fatigue, dark blotches under the skin/inside mouth, and pneumonia.3

Testing

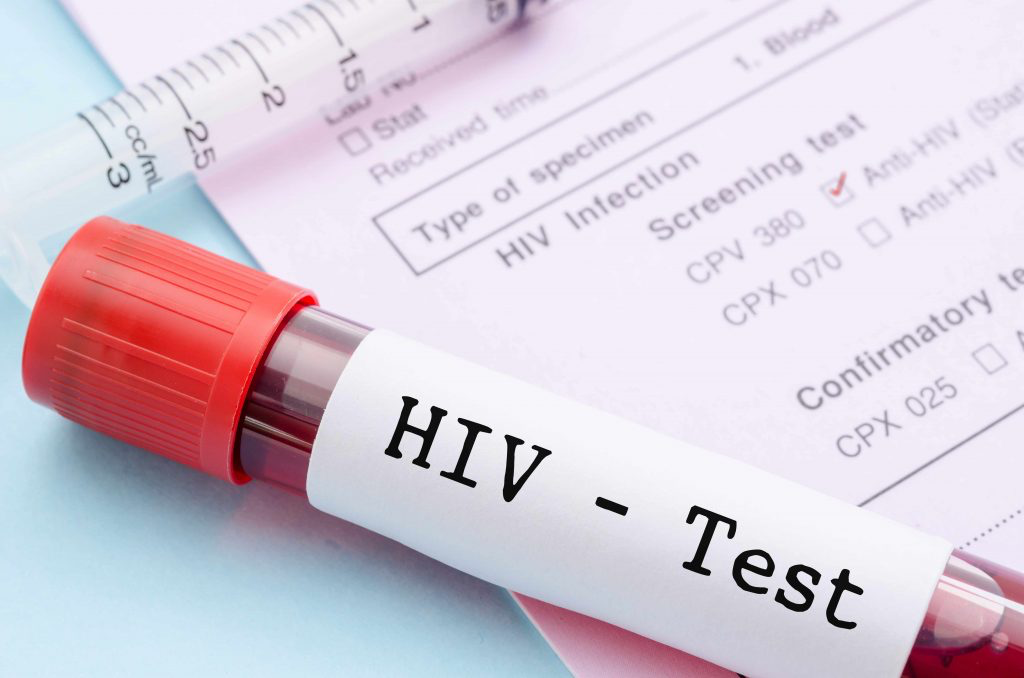

There are a few types of common HIV tests. The most common is the antibody screening test, or immunoassay. This tests for the presence of antibodies that your body automatically makes to protect against HIV once infected. This test can be conducted in a lab or as a rapid test at the location where a person is being tested. The test is generally performed on blood, as the levels of antibodies would be higher in blood than any other bodily fluid. Another method of testing detects both antibodies and antigens. An antigen is a part of the virus itself. These antigen identification tests are useful for early detection, as they can find HIV as early as three weeks after a person has been exposed. This type of testing is meant only for blood sampling, and is not available at all testing sites. A third type of test is the rapid test, which is used for screening and produces results in 30 minutes or less. It is important to conduct a follow up test, because if the rapid test is administered before antibodies can be found in the blood, it may give a false-negative, (or HIV-negative) result. Finally, follow up diagnostic testing is performed if any preliminary tests are positive. This test consists of the antibody differentiation test, which distinguishes which strain of HIV is present, as well as the Western blot or indirect immunofluorescence assay, which both detect antibodies.

There are also two home HIV tests currently on the market: the Home Access HIV-1 Test System and the OraQuick In-home HIV test. The Home Access HIV-1 Test System is a home collection kit where a person collects a blood sample by pricking their finger, and then send it to a licensed laboratory. Anonymous, accurate results may be available by as soon as the next business day. The manufacturer also provides follow up tests and confidential counseling/referrals for treatment if the test is positive. The OraQuick In-Home HIV Test involves swabbing the inside of your mouth for oral fluid, and using an in-home kit to test it. Results are generally available in 20 minutes, but this should be used with caution because oral fluid often has lower levels of antibodies than blood. Because of this, around 1 in 12 people who use this test may receive a false negative, so a follow up test is always necessary.3

Treatment

People infected with HIV can now obtain much better medical care than in the past. Treatment with HIV medicines is called antiretroviral therapy (ART). ART can’t cure HIV, but it can help patients live longer, healthier lives. These medicines also reduce the risk of HIV transmission. There are many drug classes involved in the treatment of HIV, some including Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs), Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors, and Protease Inhibitors. These drug classes block reverse transcriptase and HIV protease, which are both enzymes the HIV virus needs to make copies of itself. Combination HIV medicines, known as “cocktails,” generally contain two or more HIV medicines from one or more drug classes. A few brand name examples include Trizivir, Epizicom, Atripla, and Genvoya.3

Prevention

Currently, HIV is spread mainly through unprotected sex and shared injection drug equipment, like needles, belonging to someone who has HIV. HIV can also be spread from an infected woman to her child during labor and delivery, or breast feeding. It is not possible to contract HIV from casual contact, as the virus is not air borne. Also contrary to popular belief, HIV cannot be contracted from handshakes and hugs, or using toilet seats, door knobs, or dishes used by a person infected with HIV. There are a number of ways to reduce the risk of contracting HIV:

- Getting tested with a partner: Communication is important to a physically and emotionally healthy relationship. An open conversation about getting tested can keep communication lines open, and can prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS.

- Using barrier methods of protection. Currently, the CDC (Centers for Disease Control) estimates that the most common route of HIV/AIDS infection is unprotected vaginal or anal sex. Using barrier methods prevent the transmission of virus through genital fluids are a very accessible and reliable way to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS. Some examples of these include dental dams, female condoms, and male latex condoms.

- Getting tested regularly, especially if you have multiple sexual partners, is another important way to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS.2

- PrEP: PrEp, or Pre-exposure prophylaxis is an HIV prevention option for people who do not have HIV but are at high risk for being infected. A brand name example is Truvada, which is a medication that is to be taken daily for the prevention of HIV contraction. Truvada is a combination of antiviral drugs that work to prevent HIV cells from multiplying in the body. 4

- PEP: PEP, or post exposure prophylaxis, may be administered to reduce the risk of HIV infection in someone who has already been exposed. To be effective, PEP must be started within 3 days after possible exposure, and must be taken every day for 28 days. If taken correctly, there is about an 80% chance of not contracting HIV. 4

Concluding Remarks

It is important to remember that while public perception may associate HIV/AIDS with the LGBT community, that is simply not the case. HIV/AIDS can and has affected many different populations. This is why accurate information and quick response to possible exposure is so necessary. In the last few decades, HIV/AIDS has gone from a death sentence to a livable illness. Due to new drug cocktails and better illness management methods, people with HIV can now live full and healthy lives.

Check out this video below to learn more!

References

1. “HIV/AIDS.” Welcome to AIDS.gov. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Nov. 2016.and Prevention, 2016. Web. 17 Nov. 2016.

2. “The Basics of HIV Prevention | Understanding HIV/AIDS | AIDSinfo.” U.S National Library of Medicine. U.S. National Library of Medicine, n.d. Web. 16 Nov. 2016.

3. “HIV Treatment. FDA- Approved HIV Medicines| AIDSinfo.” U.S National Library of Medicine. U.S. National Library of Medicine, n.d. Web. 16 Nov. 2016.

4. “Truvada: Uses, Dosage, Side Effects- Drugs.com.” Uses, Dosage, Side Effects – Drugs.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 16 Nov. 2016.

Last Updated: 29 November 2016.